Trying to establish a representative interview with Jim Keltner requires a sense of humor. The way he plays drums and the way he is seem to be so alike. Talk to Jim on Monday about drum heads, for instance, and you’ll get a different answer than you would if you asked again on Friday. We conducted this interview on and off for several months, putting the finishing touches to it only weeks before publication. We spoke about the early days, the crazy on-the-road days, his diverse drumming styles, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Jim’s family, all the way to equipment references. Putting this all together, I realized one of the qualities that make Jim Keltner a great musician. It’s the same quality one finds in the musicians he plays with. The quality is heart. Kenneth Patchen once wrote, “Be assured—whatever happens, I won’t lie to you. One ends by hiding the heart. I say here is my heart, it beats and pounds in my hand—take it! I hold it out to you…” Jim Keltner is like that.

JK: My father bought me an old, used Slingerland set, which I wish I had today. The snare drum was practically the same as one I’m using onstage. It’s an old Radio King restored by Paul Jamieson here in Los Angeles. He’s done one for all the drummers here in town. Everybody has at least one, I think. If I had that Radio King shell I’d give it to Paul, he’d fix it up for me and it’d be a great old drum! But I don’t know where the set is now. Somebody’s garage probably.

SF: When did you first know that you wanted to be a professional drummer?

JK: It sort of crept up on me. I always wanted to be a jazz drummer. That’s the only kind of music I liked when I first started playing. I really hated rock and roll. Then it dawned on me after awhile that I wasn’t going to be able to make it as a jazz drummer. Basically, because I wasn’t another Tony Williams, Elvin Jones or Jack DeJohnette. I started doing demos and I felt like it came real easy to me. Then they always complimented me on the sound of my drums, because I was copying Hal Blaine.

SF: As far as actual tuning of your drums?

JK: In terms of tuning and the way I played, because Hal was playing on all the hits that I was starting to listen to at that time. I just became very intrigued by the whole rock and roll studio drumming thing. When people started complimenting me, saying, “Hey, you sound like Hal,” that’s the best thing that happened. It gave me a lot of confidence and I kept on going. It was Albert Stinson who really turned my head around about jazz. Albert was my very closest friend in life. When we first got out to California in 1955, I was thirteen. I met Albert when I was fifteen, and we played together for a long time. He was a bass player, and we were like Charlie Mingus and Dannie Richmond. We had a little rhythm section going, and we played occasionally with people like Bobby Hutcherson. Then Albert went off and became a huge jazz player. Miles Davis wanted him at one time. He played with all the jazz players and they all loved him. He died June 2, 1969 in Boston. I was in New York at the time with Delaney & Bonnie & Friends.

Albert had moved to Westchester, New York to be with his family. During that year he first moved, I got very depressed because he was gone. He was my only touch with jazz. When he split I just didn’t have anybody to play with anymore. That whole year seemed like a lifetime somehow. So the year that he was gone, I really got heavy into rock and roll and joined Delaney & Friends. When I got back east, I saw Albert. We spent a night hanging out in New Jersey and had a great time. The morning after the next night, his girlfriend called me and told me that Albert had died in his sleep. It pretty well turned everything around for me. Bill Goodwin came down to the club that night and we shared our misery and pain. Bill’s a fantastic guy. I’ve always loved the way he plays.

Albert used to say, “Check it out sometime. Different personalities in people affect their playing. They play pretty much like they are.” That’s very true. Look at Buddy Rich!

SF: People say, “Gee, it’s a shame that Buddy Rich is the way he is. He plays so well.” If he wasn’t the way he is—he wouldn’t play like that!

JK: Let me tell you something about Buddy Rich. Everybody says that he’s real conceited and you can’t talk to him, right? A few years ago, Emil Richards took me and my wife to see Buddy play at a musician’s night in a restaurant in Glendale. All the musicians in town were there—especially drummers! So after his set—which was incredible—we all went back to see him in the dressing room. I’m just watching him sitting there and talking and having been buzzed on how he played so incredible. He looked real small and kind of vulnerable. So I went over and I said, “Can I kiss you, man?” I reached down and kissed him on the cheek. Everybody in the room was thinking, “OH SHIT! WHAT’S JIM DOING? HE’S CRAZY! BUDDY’S GONNA KILL HIM!” But he was so gracious and beautiful. He understood where I was coming from. He could feel what I felt in my heart, you know. He is an incredible man. Everybody’s got a reputation of some sort if they’re in the limelight at all.

SF: When you wanted to be a jazz drummer, did you practice and strive to become technically proficient?

JK: Well, there was a guy named Michael Romero. This guy was playing in Los Angeles, all around, just like Albert and he was so intimidating to all drummers. Old, young, great drummers—whatever! He was just great. He had chops that wouldn’t stop; he had a conception of how to play, he had everything together. After seeing Michael play a bunch of times I remember I almost just threw it up. Albert said, “Hey man, don’t worry about it. This guy’s got a lot of chops; he can play but don’t worry about him. You got your own thing. You play like Dannie Richmond. It’s okay.” I would see Billy Higgins play a lot. He blew me out. I became an instant Billy Higgins fan. He played a lot simpler than most guys, but had a groove that just would not stop!

I practiced a lot, but mostly listened to records. Every time a new Miles or a ‘Trane record would come out, I’d get it and we’d all sit around and check it out. I always wanted to sound like the drummers I heard more than I wanted to know what they played. A certain amount of technique is necessary to pull that off”, so I practiced pretty hard. I used to play on a pad on the coffee table in front of the TV. I’m thinking of taking a few lessons again.

SF: It sounds as if Michael was somewhat of a local folk-hero.

JK: Possibly so. He had a point where he was definitely the hero. He had a real East Coast sound. We had a great deal of respect for some of the principle West Coast players, but basically the East Coast was where it was at. Michael never had a really clean sounding snare drum. It always sounded kind of sloppy. But his technique was so great that he made it work beautifully. There are a few guys around who remember him. Most of the rock people don’t know.

SF: So you grew up when rock was in it’s infancy.

JK: Yeah, I was able to see Elvis for the first time on TV. Elvis always did kill me. My sister—who is 5 years younger than me—played a lot of the current rock and roll at the time. That stuff used to drive me up a wall. I used to constantly belittle her. I’d say, “Hey, I’m gonna break your record.” I started turning my whole family into jazz fiends. It worked to a certain extent, but then they had the last laugh.

SF: Was your gig with Gary Lewis and the Playboys your first studio shot with a band?

JK: That was in 1965. I had been with Don Randi playing six nights a week at a little club called Sherry’s. I really enjoyed playing with Don, but Gary Lewis offered me a lot of bread; $250 a week, to play drums so he could step up front, play guitar and sing. My first real rock recording was with Gary. “Just My Style” was the hit from the album. I was only with Gary about seven months. After that I played with Gabor Szabo; then John Handy for a minute, then in a group called Afro-Blues Quintet + 1, and then a group called MC:. I did a lot of demo recordings in 1967 and ’68. I spent most of ’69 with Delaney and Bonnie’s band. In March of 1970 I did a two month tour with Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen, and directly after that tour I started recording in the studios almost full time.

Another drummer I want to mention is Gene Stone. He and Larry Bunker both played with Clare Fischer’s group which was an exciting band at the time. They switched on and off, and it was a great contrast in styles. Gene had a real easy way of playing that really influenced me a lot. I related to him real well. That’s kind of the way I started trying to play myself. To hear him on record you’d know what I’m talking about.

SF: When you were frequenting clubs like Shelly’s Manne-Hole, were you able to talk to the established drummers? Were they receptive to you?

JK: Shelly was the easiest drummer to talk to ever! He’d talk to anybody about anything. I even called him one time and his wife woke him up to talk to me. I said, “Oh no, no. Don’t bother.” She said, “That’s okay. He’d probably like to talk to you.” So Shelly got on the phone, sleepy, and I said, “What size hi-hats do you use?” He just ran down the whole thing and was beautiful. He answered all my questions. I was always intrigued by his great cymbals. He and Hal Blaine are the two most amiable people you’ll ever want to meet. They love having company. I’m sort of the opposite. I keep just with my family here. Not really a recluse. We’ve got enough entertainment going on around here with three kids.

SF: I’ve always felt the family was important. It used to bother me hearing all the horror stories about the difficulties of being a musician and keeping a family together.

JK: I’m considered a rarity in that respect because I’ve been where I’ve been and done all the things that I’ve done and I still have my family together. That’s what hurt so bad about John Lennon. Everybody calls him the genius that he was. So prolific and down to earth just to have that ability to lead people without trying. John didn’t care about what people called him, or what people thought he was supposed to be doing. That new album! Whether you like Double Fantasy musically or not—however you feel about it, it’s John singing from the gut. Those songs about his family and about how happy he was? God Almighty! That’s an incredible thing! How many artists would have the courage to do that? “Hey, here’s the genius coming back! What’s he going to do?” And he talks about changing diapers and how much he loves his wife. Good Lord!

You’re very fortunate if you can have a family and maintain it through all the things a musician goes through. I’m actually fortunate to still be alive after some of the things that I’ve done through the seventies. I was really hard on myself. I guess at one point or another all of us were. It’s a real great thing to be able to sit here and talk and still have a family intact. One of the things that John enjoyed was that I had my family together all the time. The few times he was here, he really enjoyed it and felt real comfortable with the family situation.

SF: Do you do any teaching or clinics?

JK: I wouldn’t want to right at this time. I have a real hard time even helping my kids with homework. I just don’t have any patience. I was teaching in 1961 at a music store for awhile. I enjoyed it, except my lack of patience got to me. I would have moms calling me up asking, “Hey, what did you do to my son? He came down to the car and he was crying?” I would say to a student, “Look you’re not fooling anybody. Your mom is paying hard-earned money and she thinks you’re really interested in this. You tell me you’re interested, you go home, spend a whole week and then you don’t know the lesson at all! You can’t fool me. I know you didn’t practice.” And the kid would cry. In some cases it worked and in some cases it didn’t. Another thing, I taught a little kid named Jackie Boghosian. We’re still in contact. He’s a psychologist or a psychiatrist now. He probably had as much talent as anybody I’ve ever seen. I was 19 at the time, and he was ten years younger. He could do things I couldn’t do! I’d be teaching him but he’d be showing me little things that I’d cop from him without telling him. I had to be the teacher, you know. But his folks had bigger plans for him; they wanted him to be a doctor. So they got their wish. I’m sure he’s happy, that’s the bottom line, but that kind of blew me out. He was so talented. Right now he could be one of the greatest drummers around.

SF: How would you advise a drummer who wanted to get into the studios?

JK: You talk to any studio player on either coast—anywhere—and they’ll tell you pretty much the same thing. You’ve got to be in the right place at the right time, and it’s luck. Obviously you have to be able to provide what the people want. You’re working for producers when you’re in the studio. They’re either producing a film, record, or a commercial and it’s those people that you work for. Attitude has as much to do with the studio as your playing ability. If you go in and you’ve got in mind, “Hey, I want my drums to sound like this,” or “I want to play my own thing,” then chances are you’re going to limit yourself. The studio scene is definitely geared toward the producer. You’ve got to deal with the engineer, the artists and other musicians, so it’s definitely attitude along with playing ability. But the bottom line is the producer and what’s best for the song.

Nine times out of ten, my drums are going to sound like the engineer, the producer, or the artist wanted them to sound. It’s not necessarily what I would choose myself. If it works for them—it works for me. In striving for hit records, the producer and engineer have a tendency to check previous hits and copy these sounds, although many times the musician will try to copy something he likes. I have many times. Sometimes it works, other times it doesn’t. Also, every studio has its own personal acoustical sound and feel. You may find that one drum that sounds great in one studio might require an altogether different tuning to sound great in another studio.

I was speaking the other day about a comment someone made that all drummers sound alike today. That’s not al ways the drummer’s fault. I was in church once watching our kids sing in the choir. They had a little band playing with a full orchestra, and three choirs. It was beautifully done. They had a rock drummer playing some of the contemporary gospel things and he was a good player, but his drums sounded horrible! It sounded like he was trying to copy that “studio sound.” He had no bottom heads and his drums were tuned low with a lot of tape on them. Somebody should’ve told him, “If you’re playing live, make the drums sing if you can!” I have heard good sounding one-headed toms, but I suppose just like with doubleheaded drums you need to take the time to get the best out of them.

SF: Is there any difference in your set-up and your tuning when you’re in the studio and onstage?

JK: A little bit. I like to have my drums totally wide open when I’m onstage. Not real ringy, but at least so that they have a tone. It depends on the kind of band you’re in and the kind of music you’re playing. Everything is relative. There are no set things. A guy called to ask me what kind of heads I use, and what kind of snare drum I use. I said, “Well, I have 17 snares.” Not to be bragging about how many drums I have, but over the years I’ve collected that many and I’m a drum fanatic. I love drums with my heart. I appreciate a well-made drum, so when I see one I’ll do anything I can to get it. I was that way when I had no money at all. When my wife was working and I was doing Bar Mitzvahs and Mexican weddings for $15 to $25 a shot, I would make sure that I would somehow do something to get a cymbal or a drum. Then I never sold them or traded them in. As a consequence I have a lot of equipment. Seventeen snare drums just gives me a choice. I use them for different things. It’s like asking, “Who’s your favorite drummer?” That’s impossible. If I tell somebody that I’m playing one kind of drum head today, later on tonight I may make a discovery that another head is better. Generally, I like Remo Ambassadors or Diplomats on my snares, and almost anything on the tom toms. I make a new discovery of combinations every so often. I’m constantly changing things around. But I only use Remo heads or an occasional calf head.

I feel that I have to tune the drums to some kind of way that makes sense to me. I don’t tune in intervals. It’s too predictable for me. I don’t like anything that is that predictable. I purposely screw-up my drumset sometimes to create a change of attitude. I love it when the cartage people set up the drums all wrong; maybe a small tom on the right and a big tom on the left. When I’m playing with two or three tom-toms, I think of a melodic scale. I get bored with the same old descending tones in perfect thirds or fourths. It’s nice for things to be a bit weird to make your attitude change.

SF: What kind of sticks do you use?

JK: I used Gretsch 3D sticks for years. Then I wanted a little heavier stick so I went to Regal 5A, then to 2A, then to the Pro Drum AB stick which is just a bit too long for me. Now I’m using a Regal Rock stick which is a little like the old Gretsch 3D. But it’s like when I go to buy a coat—it’s either too big or too small.

SF: Have any of the companies considered making a Jim Keltner model stick?

JK: Yamaha would do that. I’m sure. I don’t think I’d really want that because I’d be afraid if I didn’t dig it, there’d be thousands of sticks all over with my name which I wouldn’t be using at all. I change in a second. I need a stick that’s just about the same weight as the Regal Rock stick, but a tiny bit fatter and about 3/8″ longer. Maybe Regal will read this!

SF: How do you feel about matched grip versus traditional grip?

JK: I started off playing with convention al grip. I started using matched grip for more power onstage. It got to the point where I was playing matched grip in the studio all the time, also. But I always felt that I was cheating myself because I had such a nice technique with the conventional grip. When I’d switch back to the conventional grip I’d feel a little weaker, but I felt funkier. I always feel funkier with my conventional grip. In the last couple of years I’ve been changing back and forth to where I can truly say that I feel comfortable playing both ways. It’s a real nice feeling to be able to switch back and forth. That’s what I would advise anybody that’s got a problem with it to do, especially if they already play conventional grip. I think it would be good to just go ahead and get right into matched grip and just do it. Make it really happen. I would tell drummers that have been playing matched grip and have a nice technique, that want to switch over to conventional—don’t give matched grip up entirely. It does work. I’ve proven to myself you can do both. I really didn’t think I could. I thought it would be too much of a conflict, but that’s not true. I’ve had people tell me you can’t roll with the matched grip. So I learned how to roll with the matched grip! I can do anything with the matched grip that I can with the conventional grip.

Another thing, in that Modern Drummer story on Ed Greene, Ed was talking about how he sits low on the drum stool. That interested me because I’ve always sat fairly high up. Jeff Porcaro sits very low and so does Hal Blaine. Shelly Manne told me that years ago, but I’m just now discovering it for myself. I said, “I’m going to try this.” I set the stool down a little lower and I got a better feeling from my foot than I’ve had in a long time.

SF: Whatever happened to your band, Attitudes?

JK: That was a very short-lived band, mainly because the members were all really hot-shot musicians. David Foster, the keyboard player, is now producing everybody in sight. He’s an incredible keyboard player, a great arranger, and a great songwriter. He co-wrote, “After The Love Is Gone” by Earth, Wind and Fire, which is one of my favorite songs ever. He didn’t have time for a band after awhile. The guitar player, Danny Kortchmar, is producing albums now and making his own records. Paul Stallworth is writing songs and doing session work in North California.

SF: How do you keep your own attitude right?

JK: In the last year and a half, since I’ve really sort of opened up my heart to the Lord, that’s really made a great change in my life musically as well as personally. I find that I have more fun now because I remember things. I don’t go to sessions and forget what I did afterwards because I was so stoned, and my playing is generally better. I look forward to trying new things. I learn something new from each session.

SF: Do you choose your own mic’s in the recording studio?

JK: I admire drummers who do get into that, but I never got that deep into it. I did a Direct-To-Disc record for Doug Sachs recently that should be coming out pretty soon. There are two different drummers—one on each side—playing solo drums for stereo equipment testing. Doug has been talking to me about this for the last 5 or 6 years. I would always say, “Oh, that sounds like a great idea,” and shy on it, mostly because I was afraid. I didn’t want to sit down and play drums alone. I’m very afraid to solo. I suppose if I had done more solos early on it would be more natural to me now. There are a lot of drummers who love to solo, but a solo is real foreign to me. I’ve never been able to, and never thought I wanted to.

In the last year and a half, I have this feeling that everytime I get scared of something—you know—it says in the Bible, “Lay your burdens down at my feet and I will take them from you.” I do that, man. It was always just words to me before, but it works in my life. It’s working slowly and it’s getting better all the time. When I get afraid of anything now I just pray. I’ve always prayed all my life, everytime I’d sit down behind a set of drums. Especially sitting down behind the drums. I had this little short prayer that I’d pray, real fast. I still do, only now I pray differently. It’s funny, there’s just all these things to learn in life. Consequently, I did this thing for Doug Sachs and I had great fun!

I borrowed a snare from Mark Stevens. He showed me this little 5-inch maple snare that Pearl made and it just looked so clean to me. So we set it up and I played on it and really dug the way it felt. Mark’s real great about loaning me things, so I borrowed that drum for the Direct-To-Disc record, and I had a ball with it. It made me feel like playing, even though they made me tape it up while there was no reason for it. I enjoy having to play occasionally on a rental set, or a makeshift set. Sometimes it makes you think a little different.

The reason I brought this record up, is that Doug Sachs and Bill Schnee (engineer and producer) are two microphone geniuses. They make their own. Mark Stevens is a drummer that’s into mic’s. I’m just not electronically minded I suppose.

SF: How did you develop your reading?

JK: I took basic reading lessons when I first started playing with Charlie Westgate in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He’s the guy that wrote, “The Downfall of Paris.” He and my dad were both in The Shrine Drum Corps in Tulsa. I more or less started by playing on my dad’s marching drum. I’d have my sister play the bass drum part on the edge of the snare drum with a spoon. She would go tap-tap-taptap, and I would play all the little hot licks and all. Charlie showed me the basics and how to count quarter notes, eighth notes, and sixteenth notes. From there I joined the school band and from there I sort of taught myself. I never got into chart reading until I started reading charts. So I learned how to read charts on the job.

SF: Did you ever run into a chart that scared you?

JK: Oh, of course. Shelly Manne is a tremendous reader. I read somewhere where he would sit down and look at a part and would say, “Oh, I’ll never make this,” and he’d sail right through it. I felt the same way with a few Roger Kellaway charts in front of me. He loves wild time signatures and all. My first real challenge with odd time signatures was a record I did with The Baja Marimba Band. Roger did the writing for this particular album. My friend Emil Richards was on the date and he’s a monster at reading. He helped me on that date. There would be a bar of 13/4, then a bar of 15/8, then maybe two bars of “A, and the whole groove would basically be in 7, and then there’d be a little % bar followed by a 5/4 bar two measures later.

SF: You were expected to sight read that?

JK: Oh man! I knew I wasn’t going to be able to sightread it. My only hope was that somebody would break down here and there or that the trombone player would make a mistake, then they’d have to stop and I’d be able to figure it all out. It was so complex and crazy and Emil saw the look on my face. He came over and said, “Now look, think of it like this.” He showed me different ways of listening and relaxing rather than counting. That little insight into that, coupled with being able to run the tune down 3 or 4 times enabled me to get through it and make it feel good. Each time you’re able to make something like that happen, your confidence goes way up. It’s a real great challenge. I love reading. I love doing film dates and jingles. I’ve done a few things with Lalo Schifrin. He writes some pretty strange stuff.

SF: That’s interesting that you’ve worked with Roger Kellaway and Lalo Schifrin. Do you feel you’re primarily known as a rock drummer?

JK: Oh, absolutely. Larrie Londin is a real good friend of Mark Stevens, and they hang out when Larrie is in Los Angeles. I had lunch with them one day. Larrie said, “Some people in Nashville told me that you couldn’t read a note.” I told him I did. I probably have a reputation for not being able to read, and just being a rock and roll drummer that plays way back on the backbeat. Laid back, and all that nonsense.

SF: What’s your role in a band?

JK: Well, for a drummer playing in a band he’s got to be supportive. He should make the time feel good and try not to play fills just for the sake of filling available space. That’s one of the reasons I love Charlie Watts so much. But there are as many ways to approach drums as there are drummers. I believe that our individual muscular frames affect the way we make a drum or a cymbal sound. There are no two drummers with the same muscle structure or density. A drummer truly plays with body and soul and is unique in every way. That’s famed biochemist Dr. Roger Williams’ theory on biochemical individuality and it’s true.

SF: In all your years of playing you’ve never had the urge to let loose on stage?

JK: I never have. I don’t like to solo, although I love to hear a good solo. I hear some drummers saying, “I hate hearing drummers take a solo.” I always get something out of a solo. If he has the guts to take a solo then there’s going to be something of interest somewhere along the line, whether it’s 100% interesting or 10% interesting, at least that 10% is worth listening to. I’ve listened to Steve Gadd take solos and they’re so intelligent, beautiful, and so well done and thought out while he’s playing. He’s got a tremendously fast mind. I’ve heard drummers in little pickup bands in Disneyland play solos that would blow me out.

A supreme drum soloist that not too many people talk about is Ed Blackwell. When he would solo it wasn’t like a drum solo. It was like a melodic instrument playing a song.

SF: What’s the difference between playing a session date with Roger Kellaway or Lalo Schifrin, and a session date with John Lennon or Ringo Starr?

JK: When you do a rock album with somebody like John Lennon, there are songs. There are no charts really. If there’s any chart at all it’ll be a little chord chart. When I did an album with Yoko, she had a sheet of paper with the words on it in poem form. It was actually very good that way. I remember thinking, “Hey, this makes a lot of sense.” There was nothing different about the music where I needed a drum chart, but with the words written like that, done pretty much the way she was going to sing them, it made a lot of sense.

With Kellaway’s music or any great arranger, or a film score—even a lot of commercials—they’ll have an actual drum part with drum notation: tom-tom part, snare drum, bass drum, hi-hat, cymbals. That can be a lot of fun. I enjoy doing commercials because it’s a challenge to put it all together and do it exactly the way the guy wrote it. If the guy’s any good, if he really knows what he’s doing, the part will really make sense. In some cases when you try to play a part exactly as written, it’ll be awkward and you’ll want to change it.

There are arrangers who really have it down good. They’ll write the part out, note for note knowing in their heads how it’s going to happen with another part that will make sense. I love doing that because at that point you’re relying totally on your ability to read and it’s great. There’s no real sight reading thing happening in the studios. There’s no such thing as that, really. That’s not realistic. There are many, many times when a first take is made. I’ve played on many first takes that’ve either been hit records or been the actual product that ends up on the film. But that’s not a rule! You don’t go looking for first takes. That just happens by accident. There’s plenty of time to get it together. You don’t have to sightread. The better you are at sightreading, the better reader you’re going to be. Period! If you’re doing a commercial or a filmscore and the reading is very difficult, you’re going to have a chance to run it through several times to get it right. If you can read at all, those several times are going to be very helpful.

I took about six lessons with Forrest Clark, mostly to get my hands straight. I had a real bad hand habit. My left hand was all turned over backwards. I played sort of with my palm facing up. It didn’t make any sense. As a consequence I had no power and no control. I knew I had to get it straight. I went to Forrest and he helped me a great deal. I went on myself and developed a nice finger technique exercise. It gives me a good feeling of control. I love to just sit down with a pair of sticks and practice this exercise. Nothing is moving but my fingers. It’s for control.

SF: I know you have some strong feelings about “the road.” Could you suggest any “do’s” and “don’ts” for drummers who are considering going on the road?

JK: I don’t know what I could say about that without sounding like a mother. A drummer is so physical with the instrument—we strike the instrument in every way. It’s us we’re playing, basically. So you’ve got to remember that it’s your body and soul that’s making this music. Your body and your soul. If you screw one of them up. with drugs or too much booze, you’re defeating the whole purpose of making the best music you can. I’m a testimony to that. I can listen to some records that I’ve played on where I’ve been recorded playing with a band live, and I’m so wiped out from various combinations of drugs and booze that it doesn’t sound good. I don’t understand how I could’ve disgraced myself in such a way. It’s things that maybe I got by with at that time. Maybe there’s a way today that people feel they can get by with it, but basically you’re not getting away with anything. You’re killing yourself slowly. All drugs and alcohol are spirit killers. They kill your body slowly. But more importantly, they kill the spirit within. They’re all a bad trick. You take a certain kind of drug, maybe in combination with alcohol and you think. “Ah, this is it! This is the combination for me because I played my ass off last night.” There’s always going to be a little isolated thing which you did great, but it’s never going to be—and this is from personal experience—because of a chemical combination. If you keep on trying that same combination, you’ll find out real quick that the combination is not magic. It’s a trick. A trick on you!

If you’re going on the road you should treat your body even better than you do at home. You should do some running if you can, or a lot of walking. Some people don’t like the road. They would rather stay at home and work. I was like that for years, but it was mostly because of my bad habits and missing my family so much. I’ve been fortunate recently to have my whole family, or part of my family, on the road with me from time to time.

I’ve always had this fascination for places like upstate New York where they have those little stick houses and the stick trees in wintertime. I get a car and drive and see those places. It just knocks me out. Or being down in New Orleans, San Antonio, and walking along those little canals they have. Omaha, Nebraska, for God’s sake! Bob Dylan and I went for a walk in sort of a semi-blizzard in Nebraska all wrapped up. I just love it! If you really take good care of yourself and you have a good purpose for being on the road, then you’re going to feel a lot better about it. I like to walk around the cities, check out the people, go to stores, look in pawn shops for cymbals. That’s one of my favorite things. That’s another reason why I ended up with so many cymbals, snare drums and things. You can buy stuff real cheap in the Midwest, and something you may never find in Los Angeles or New York. People say they get on the road, they get bored and that’s why they take drugs. There’s no reason to be bored on the road if you really do it right. I don’t know if this comes with age or what, but you have to learn to respect yourself. You’ve got to respect the body that you’ve been given and the mind that you have. If you think you’re good musically—all the more reason to make it better than good rather than trying to kill it. That’s coming from first hand experience.

SF: What do you like to do when you’re not playing music?

JK: Well, I like to read and I like working in my yard. I can’t read novels anymore and I used to do it all the time. I went from novels to reading autobiographies and then “real” things, like documentaries. The last good book I read was The Gentle Tasaday, about this group of cave people in the Philippine Islands—the last known cave people to have been discovered. I savored that book—every word. I didn’t want to put it down. I hated it when it was over. From then on I couldn’t read anything except things about people. The only things I read anymore are the entertainment section of the newspapers and the Bible. There’s an awful lot of good stuff in the Bible from the beginning to the end. I’ve got a lot of reading to do there. Also, Bible Study classes are lots of fun and very necessary.

I’m trying to use my time more wisely. I like to try to do things with my family if I can. I don’t go to parties as much as I used to. I like to play bebop jazz on the side.

SF: Where do you see yourself in the next five years?

JK: I would like to possibly get a project going of my own. Producing or doing my own kind of album. I have in mind a “sound” album with some funny bells that I’ve run across that I like playing. A combination of bells and drums and singing, if you want to call it singing. I have a lot of fun. I do these things in my room and I put them on tape, and my kids and my wife hear them and they love them. It makes them laugh.

SF: Do you write songs?

JK: I’ve got a publishing company and I’m listed as a writer and I’ve co-written several songs. Yes, actually I have written a couple but I haven’t gotten that serious about getting them down. I’ve been told that they’re good enough that I should do that. I’m not real great at lyrics. I’ve been told by some of the greatest songwriters in the world that I should write because I have a colorful way of talking sometimes, and all I have to do is write about my experiences. It just doesn’t come easy to me. I think it’s a matter, probably, of forcing myself to get down and do it. It’s basic insecurities in me that make me not appreciate a lot of the stuff that I’m good at. I think most people are that way to a degree. You have to learn to develop a respect for yourself in a lot of ways.

I’m fascinated how most great songs are usually so simple in their basic structure, and how some songs are basically self-arranged while other songs seem to need a lot of work. Donald Fagen (Steely Dan) says that when he’s trying to record one of his songs with players that he wants, who are not able to get the basic track down within a few takes, he says he figures something is wrong with the song. He puts it away and moves on to something else.

You know that great article in MD on weightlifting? I loved it. That was something I always had questions about. I worked out for a long time as a teenager and I thought it did me good. Then I started feeling guilty that I was stretching muscles that I shouldn’t be; that I was hurting myself somehow in my playing. I wasn’t real sure. Nobody could really tell me. Who knew? I’d talk to one drummer and he’d say, “Oh my God. Don’t do that man, you’ll hurt yourself. Practice only with the sticks that you’re going to use on the gig.” Then I’d hear another drummer say, “Well, I practice with these baseball bats and that helps me.” I never knew one way or the other. So, that article was great to read. Now, I don’t feel so bad when I feel like lifting some weights. Occasionally I have a craving to do that. My body feels like it needs to get tight. My son and I will work out together.

Another thing I’d like to share: occasionally I’ll go out in the backyard and chop down a cactus. I never would chop down a tree because I love trees too much. I plant trees all around my house. There are some huge cacti. This is California, it’s a desert. They grow real fast and I have to chop them down from time to time. I get out there with an axe, I swing away, chop like crazy and it makes me feel good all over. I get real hot and warmed up. A few times I’ve come upstairs directly from chopping and played the drums and I have so much speed, facility, strength—it’s just incredible. I always wanted to share that with somebody.

SF: Could you give us a rundown of your present drum set-up?

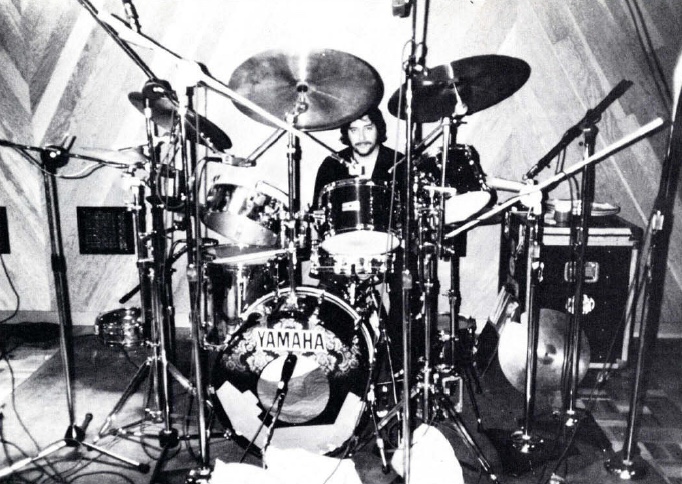

JK: Sure. I’ve been using Yamaha drums since about 1976. I have four sets. One is a blue prototype set. It’s one of the first sets they made, I believe. Because it was a prototype, I’m just now beginning to discover some things that were wrong with it and I’m having them corrected at Don Lombardi’s Drum Workshop. For example, I had all the tom-toms trued. I’ve had the entire set done and also I’ve done that to my second set, which is a chrome Yamaha set. I had it done after I read the article in Modern Drummer on truing shells. The last two sets I have are black. Jeff Porcaro had the same kind of finish on a different make set and he called it a “black Steinway” finish. It’s almost like a piano finish, so smooth and beautiful. It’s the same set Steve Gadd has but the lugs on Steve’s set are the original lugs which stretch all the way across the shell. I have conventional lugs. I figured it would be better to have less metal touching the shells. They sound good. They’re made better, they sound better, and I didn’t have to do as much work on them as I did on the other two sets.

Mostly I use a 12″ tom-tom on the left, and the right tom-tom varies from a 10″ to a 15″. Sometimes I have them all backwards, like a 12″ and a 10″, or a 12″ and a 14″, or a 12″ and a 15″, but usually always a 12″ on the left.

SF: But primarily, you’re using a double mounted tom-tom kit?

JK: Right. However, in the Yamaha drum catalog they have me listed as playing four tom-toms piggyback style on the bass drum. I only did that briefly to see how it felt, but it was too far to reach and felt awkward. Somebody recently suggested I try a 15″ tom mounted on a stand instead of using a 16″ floor tom. I tried it and now—at this time anyway—I prefer it to the sound of my 16″ floor toms. I used to always use a 14″ floor tom which was very easy to get sounding good. I hated 18″ floor toms for a long time. But lately, I’ve got a real good sound and feel on a couple of 18″ toms that I use in the studio. One has a Pinstripe head and the other has a Remo/Yamaha Ambassador head on the top. For now, all the bottom heads on my tom-toms are coated Diplomats.

I guess that I can’t really say that I have a particular drum set up of my very own. When the engineers see me coming they say, “Oh no! What’s he got this time?” They never know whether to expect a bunch of tom-toms and cymbals or a very simple little set-up.

A lot of drummers are just using one tom-tom on the bass drum and a floor tom. That’s the old bebop style. I kind of like that. That’s the way Charlie Watts plays and he gets all the tom-tom sounds you’d want to hear. On the other hand, the more toms you have, the more sounds you can get. I’m sure it comes down to how you handle what you have. Some people strive for taste; other people despise taste; I feel somewhere in between.

I’m using all Yamaha hardware. They make a great cymbal stand. I’ve got combinations going that are like an erector set. On one large cymbal stand base I can have two cymbals, a pair of hi-hats, and one tom-tom. On the other side is another cymbal stand with possibilities of several cymbals and a couple of tomtoms. Everything is mounted with just two cymbal stands. I can have up to six cymbals, a pair of mounted hi-hats, and several toms. I actually use two pair of hi-hats. One pair open all the time in the conventional way. Over to my right is a pair of permanently closed hi-hats, mounted on the cymbal stand. The reason I do that is because I’ve been using a double-beater bass drum pedal for about two years. I’m working with Don Lombardi on a prototype of one of his pedals. His chain-driven pedals are far superior to what I’m using now.

I don’t really use the double pedal for speed. I think there’s nothing faster or prettier than just one foot. Buddy Rich exemplifies that. Most drummers that have good technique can play great fast things with one foot, so you don’t really need an extra pedal for that. I use it sometimes for punctuation. It’s a diversionary tactic. When I put it on the drumset for the first time, I took it to a session. I said, “I’ll just put this up and screw around with it. Maybe it’ll keep me from being bored from playing the same old stuff all the time.” It changed my whole way of thinking. It gave me options. I love playing backwards nowadays. I’ve gotten real comfortable with that. I can play the hi-hat with the left hand and everything else with my right hand. I think Steve Gadd does that a lot. It’s something I’ve been toying around with for years and now it’s real comfortable. I’ll play a whole song backwards sometimes. It makes my time sound a little different and I’ll go for fills in a different manner.

As far as a snare drum goes—I’m using two snare drums at the same time; onstage and in the studio sometimes. I used it on Ry Cooder’s album Borderline. I don’t know which songs though—I’ve forgotten. On some of that album I’m using two snare drums, two hi-hats, and two bass drums. It sounds like a lot of equipment, but I try not to make if appear that way. I use it for the different sounds. Also, when I play with Ry I use another tom-tom or a Roto-tom for a timbale sound, instead of an actual timbale.

I use a 22″ bass drum live, but a 24″ in the studio which is kind of backwards from the way most people do it. I’ve been real happy with the 24″ in the studio. Mostly I use a 22″ onstage but sometimes I’ll use a 22″ in the studio. In some cases I might use a 26″ or a 28″ in the studio! I’ve got a 28″ 1930s Ludwig bass drum that’s like an old dance drum. It’s an incredible old bass drum. I used that on a lot of stuff in the early ’70s. There’s a snare drum that I have that goes along with it, a real beautiful old pale-green pearl snare, and it’s got double snares under the top head. It’s just real immaculate. I put real thin heads on it, the Mark V Diplomat. It sounds real pretty.

Stan Yeager, from Pro Drumshop in Los Angeles fixed up one of my 15″ toms into a snare drum with the tom-tom mount still intact, so I can mount it anywhere on the set! I call it a “snom.” It sounds great. Not necessarily any bigger or fatter, just real good and solid. I used it on “634-5789” on the Borderline album.

I have about 60-65 cymbals. They’re like friends to me. It’s really silly. I don’t even put them away, I just leave them out. I’ve got like 50 cymbals sitting in my room. I like to have the choice and occasionally I’ll pick out a couple that I haven’t used in a long time. I’ve checked out all the drummers over the years and what kind of cymbals they use. For me, basically, it’s 15″ or 16″ crash cymbals. I’ve got two 15″s that I really love for crashing. I’ve got a beautiful 16″, 17″, and an 18″. Those are crashes that I choose from lately and those are all new A. Zildjians. As for ride cymbals, I have a 24″ that I use sometimes, but mostly it’s a 22″. Occasionally I’ll use an 18″. Then, I like to use the swish cymbals. I’ve got a bunch of those and my favorite swish is dying right now. It’s looking at me with a big smile. The smile just keeps getting bigger—and I hate that! One of these days I’ve got to meet some of those people back at Zildjian so they can copy this for me—maybe. I’ve got a 39″ Wuhan gong also that they used in the King Kong movie.

SF: What’s it like playing drums with Ringo?

JK: Playing with Ringo is definitely a treat. He’s a much better drummer than people think he is. I’d like to get that straight if we could. A kid called me the other day asking me that same question: “Did Ringo really play on all the Beatles stuff?” The answer is: ABSOLUTELY. I think there were two songs, very early on in their career, that Ringo did not play on. Some English studio drummer did. But two songs out of their whole career?

You asked me earlier how I feel about the role of a drummer in a band. You couldn’t ask for anything better than to have done what Ringo did. To play 12 years with the same band and have that kind of success! Not just commercial success—we all got off on those records. You can hear those records and you hear great, great tasty drum things. There’s nothing to astound you paradiddle wise, or anything like that, but it’s perfect. Nobody else could have done it any better. I’m sure.

SF: Has your association with all of those great minds that you’ve played with helped you or influenced you?

JK: Sure! I’ve been so fortunate it’s ridiculous. One night after a session with Lennon, I told him that I would like to produce a record for someone someday. He said I should. He told me all you have to do is act like you know what you’re doing! I loved that. He was a genius at that for sure. Dylan is the same way in that respect.

SF: How did your gig with Bob Dylan come about?

JK: Well, that’s kind of a nice little story. I did a few tracks on an album of what they would call “Jesus music” with a Christian artist in 1975. He got several studio guys to do it. We were recording and I noticed that the songs are songs of love for the Lord, and for what He’s doing in this guy’s life. But they were real pretty songs. So I’m thinking, “This is great that this guy can do this.” Then I found out that he doesn’t make much money doing i t . He makes a living, but it’s nothing like Rod Stewart would make. I came home and told my wife about the session. She is really responsible for turning my head around as far as accepting the Lord and letting him work in my life. But at that time, I just wasn’t able to use it. When I played this session I told the guy, “There’s got to be some way that I can serve the Lord the way you’re doing it. I feel like I should some how.” I didn’t know why exactly, I just had that feeling.

Then I realized that every time you hear some kind of Christian music, it’s usually really boring. I’m sure their hearts are in the right place, but there just didn’t seem to be any way I could get involved in it. Consequently, I thought, “How in the world will I ever be able to do this?” So I just forgot about it for a long time.

One day I’m at a session at Kendun Recorders in Burbank, and I get a call from Dylan. I hadn’t heard from him in a long time. The last time I had worked with him was on “Knocking On Heaven’s Door” from the Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid soundtrack. It turned out to be a mild hit on the radio. It was so pretty, I remember crying while I was playing—the first time I ever cried while playing. We were watching the film and playing live. No overdub. The song was beautiful and sad and haunting. On the screen was Slim Pickens dying, holding his stomach, and Katy Gerrato and her soulful eyes looking sad. Dylan evokes so much emotion from certain people, and I’m one of them. So he calls and says, “I have a new album. It’s not out yet but I want you to come by and hear a tape of it. If you like it, maybe you will want to go on the road with me.”

He had asked me a couple of times before to go on the road with him and I couldn’t. I never felt like I wanted to make it. The road had never held any fascination for me, especially after all those years that I almost killed myself out there with the Mad Dogs and Englishmen, Delaney and Bonnie, and all that. It was really hard on me—physically. The road was synonymous with all things that would kill you. So I’d always told Bob, “Sorry man. I’ve got my family. I’d rather just stay in town and work.” But I always have loved him so much. The first session I played with Bob was on a song called “Watching the River Flow.” I was always very impressed with Dylan, so when he would call. I always would go down and play just so I could see him. I just wanted to see him and talk to him, and hang around him for a minute. So this time I said, “Well sure, I’ll come down and hear the album.” But I definitely wasn’t going to go on the road. I knew what I was going to do. I was just going to go down to the office—it was another chance to see Dylan.

I go down, and the secretary puts me in this little room. She says, “I’ll turn the tape on and let you hear it. Bob said as soon as you finish listening just come on up. He’s up talking with some people right now.” She turns on the tape and the first thing that happens is that I start hearing what Dylan’s lyrics are saying. The words are about the Lord again. This feeling comes over me and it just gets stronger and stronger to where I’m sitting there sobbing like a fool!

SF: That was the Slow Train Coming album?

JK: Yeah. I just couldn’t believe it. Song after song, it was just amazing! When it was all over I went and washed my face, went upstairs and said, “Wherever you want to go, whatever you want to do, I’m with you. Let’s go.” That’s how it began. I’ve been with Dylan now, actually longer than I’ve been with anybody. Almost two years.

SF: I thought it strange that you were doing the road gig in addition to the studio albums with Dylan.

JK: Lots of my friends did, too. They were all saying, “What’re you doing?” They know how I use to talk about the road. But it’s one of the greatest things that’s ever happened to me. I just pray constantly that Bob stays strong. He gets such bad press sometimes. I think a lot of that is because he refuses to talk to some of the reviewers at times. We get incredibly good press when the show is cooking. It starts to happen usually after the first night. You don’t go onstage with Bob and play a show that’s pat. You don’t have a set list or know exactly what the beginnings and the endings are, or exactly what the arrangements are. He doesn’t want that. He discourages that. It makes sense for him. The words are the most important part of his whole shot. The melodies are pretty and unique enough to hold up on their own, so what Bob needs is people to play them with a certain kind of force. No high arrangements, or at least not too complex.

SF: The same kind of approach you might want in a jazz band?

JK: I’ll tell you something about that. Speaking of jazz—Dylan plays the harmonica like Coltrane played the saxophone! I’m telling you.

SF: The harmonica solo on the end of “What Can I Do For You” is one of the best solos I’ve ever heard, on record or onstage, in any medium.

JK: I wish you could’ve heard the first time he did it onstage. He surprised us all and we just sort of had to go with him on that. That particular night was a mind shattering thing. I’ve got it on cassette. I listened to that for the rest of the tour and it was mind-boggling. The cat gets sounds and notes that—I just compare him with ‘Trane. On a harmonica? Nobody does that. But you don’t ever hear anybody talk about that in reviews. He really stretches when he does that live. He never does anything twice the same. If you hear something he does on record—that was one time only. He changes everything around. That’s very much like a jazz musician. I talked (to him about that a little bit. He said he saw ‘Trane a few times in New York, and he used to play in the same clubs on the same bill as Cecil Taylor! Dylan is a million times more musical than a lot of people realize. But he’s so subtle with it, and he does it in such a way that a lot of people don’t understand or they don’t really get it. Thank God for those who do.

SF: Are there any closing comments you’d like to make?

JK: I guess if there’s one thing that should really matter with any kind of musician—but particularly with drummers—it is to have confidence. Playing every chance you get, under every kind of circumstance will help build your confidence. Being competitive is important, but so is sharing ideas, I love talking to other drummers and watching them play. I always learn something. I get calls from drummers asking how to get their foot in the recording studio door. Some even complain about not being able to. I’d just like to say that if you really love to play, then you’ll be happy playing anywhere. The more playing experiences you’ve had will only make you more valuable as a player. Every one of the drummers I know personally who are top studio players all have al least one thing in common: Their love for playing music surpasses any need to be a studio musician.

Also, don’t worry about copying, because copying is a natural thing, as long as you don’t make it your main thing. We all copy. Don’t worry about things like sticks, heads and all that other stuff that seems so important right now. Find your own way. That sounds so corny. But anyway—that’s the whole shot! I wish I could say something really heavy. I guess I don’t have it in me.

No comments:

Post a Comment