Between 1972 and 1980,

Steely Dan produced some of the most searing and bitter pop music ever recorded. With scathing lyrics delivered by

Donald Fagen's pungent vocals, he and partner

Walter Becker's music chronicled the feelings of many who passed through young adulthood during the 1970s. At times cynical and oddly nostalgic, Steely Dan made music borne of calculated musical precision aided by high-tech studio wizardry.

The army of musicians Becker and Fagen used were eager and willing to come under the Dan's exacting standards, knowing that time spent under their demanding ears could produce a legendary recording. Indeed, the term "studio musician" may have been coined as a result of the teeming lists of credits shown on any post-1974 Steely album. The life of the hired gun now seemed even more glamorous and lucrative to young players, what with talk of making double, even triple scale. Musicians like

Larry Carlton,

Chuck Rainey,

Victor Feldmen, Rick Derringer,

Jeff "Skunk" Baxter, Denny Dias, Michael Omartian,

Tom Scott,

Wayne Shorter,

Steve Khan,

Randy Brecker,

Anthony Jackson,

Joe Sample,

Hiram Bullock,

Michael Brecker, Pete Christlieb,

Don Grolnick, and others all made contributions to Steely Dan recordings.

And the drummers? Jim Hodder, Jim Gordon, Jeff Porcaro, Hal Blaine,

Bernard "Pretty" Purdie, Steve Gadd,

Paul Humphrey, Rick Marotta, Jim Keltner, Ed Greene-some of the most influential drummers of the last twenty-five years. Songs like 'Peg' with Marotta or 'Aja' with Gadd are etched into the collective consciousness of millions of drummers.

Named after a home appliance in a

William Burroughs novel, Steely Dan began as a touring rock 'n' roll band that eventually disbanded after two albums. Fortified by two Top-l0 hits, "Do It Again" and "Reelin' In The Years," and the sale of millions or albums, Becker (bass and guitar) and Fagen (keyboards) abandoned the road but continued to write and record pop gems of sardonic wit and lush musical sophistication. They pulled amazing performances out of their musicians, and the hits continued.

Through the years their music became even more technically streamlined as Becker and Fagen, with guidance from engineer Roger Nichols and producer

Gary Katz, mastered the studio control board. Thirty or forty takes of a single song - with entirely different rhythm sections - were the norm, not the exception. Bits and pieces of different instrumentalsts' work would be lifted and spliced together, forming the ultimate solo or rhythm track. And most of this was done before the predominance of the click. WENDEL, the group's equally revered and despised electronic sequencing genie, further enhanced their control of the music. The dazzling audio quality of their finished products was second to none.

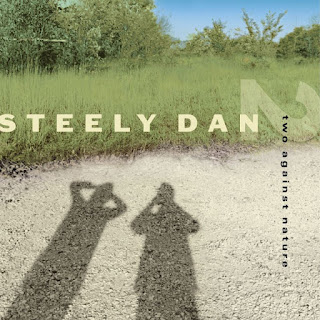

It's been twelve years since the last Steely Dan album,

Gaucho , and many drummers probably don't know what the fuss is all about, as Jeff Porcaro can attest to. "I did a clinic a couple or years ago at the Dick Grove School," Porcaro says in his groggy baritone. "The students brought CD of my stuff to play and ask me questions about. I knew what would happen; they'd ask about the 'Rosanna' beat, which is probably the most unoriginal thing I've ever done, yet I got all this credit for it. Stupid. So I brought along the CDs of the records I stole the beat from--"Fool In The Rain" from

Led Zeppelin's

In Through The Out Door, and Bernard Purdie's 'Home At Last' and 'Babylon Sisters' with Steely. Without saying anything, I put on the CD and played 'Babylon Sisters.' Half the class knew the song, but none of them knew who the drummer was. This is a class of 18 to 33-year-olds. Then I played 'Home At Last,' which I copped all the shit for 'Rosanna' from. Once again, no one knew the drummer. I said, 'Guys, it's Bernard Purdie. Who in this room has heard of Steve Gadd?' All the hands went up. 'Aja?' All hands up. 'I'm sure you all know Steve won Performance Of The Year for that in

Modern Drummer. Well. you're all fucked up! I just played you 'Home At Last' with Bernard Purdie, and that's on the same record. What do you do, listen to 'Aja' and then take the needle off? As musicians you should know everything I just played for you. Some of the best drum shit ever is on that record. Each track has subtleties."

The same can be said about all of the Steely Dan releases. Let's go back and explore each of those records, from the beginning.

When Steely Dan arrived on the scene in 1972, "progressive rock" was in vogue, with bands like Yes, ELP, and Genesis catching the fancy of many listeners. Steely surprised the rock audience because not only did they write radio-ready hits, but they had intelligent lyrics and used quasi-jazz forms (complex changes, harmonies, and structures) and jazz musicians Victor Feldman and Snooky Young--and even then they had band members who could handle all the idiomatic changes Becker and Fagen delighted in. Check out Baxter and Dias's blistering solos on "Do It Again" or Fagen's neo-ragtime on "Fire In The Hole."

Jim Hodder, "percussionist, bronze god, pulse of the rhythm section," was the original drummer for Steely. Burly, with large hands, Hodder brought a syncopated, pert style to the music. He exemplified "tasty," a common term then used among musicians to describe one who was creative but not overly flashy. His drumming seemed part BJ Wilson from Procol Harum, part Bobby Colomby from Blood, Sweat & Tears, and part Ringo. He wed lots of straight 8th notes on the hi-hat with snappy tom fills. An attention to detail is apparent from his articulate press rolls on "Dirty Work" to the rags-style bossa groove he played on "Do It Again."

"Bodhisaitva," the first song on Countdown to Ecstasy, kicks off with snare drum/hi-hat blasts from Hodder. Along with the rest of the band, Hodder's playing reflects a new looseness and confidence. Instead of striking a closed hi-hat with the tip, more of a swinging bash is employed, using the shank. He's more aggressive, playing Richie Hayward-ish fusion on the sci-fi "King of The World".

Like

Idris Muhammad or Herbie Lovelle from the l960s Prestige-era jazz recordings, Hodder maintained a snakey, slinky touch. He's still playing rock, but with a jazzer's approach. His drums are tuned a bit lower; and the cymbals seem to ring more, matching the Indian flare of "Your Gold Teeth" or the country twang of "Pearl Of The Quarter." However, this was it for Hodder as far as Steely Dan was concerned. Though a strong drummer and timekeeper, he lacked the definitive personality that might have kept him on Becker and Fagen's first-call list.

Nonetheless, Countdown is the album that set the course for Steely Dan. They continued to refine and redefine their music with each successive album, becoming more exacting and demanding with the performances and the overall sound, while writing more stunning compositions.

This album featured the hit "Rikki Don't Lose That Number" a bluesy bossa nova that borrowed from Horace Silver's "Song For My Father." The writing on this album is more expansive, with nods to country music ("With A Gun") and jazz (a surprising, note-for-note rendition of Ellington's "East St. Louis Toodle-oo"). With Pretzel Logic, the studio became an instrument, the sound was richer; and they used full orchestration with horns and strings.

The drummer for the bulk of the album was studio musician Jim Gordon. Tall and good-looking with curly blond hair, Gordon was technically gifted and possessed a golden sense of feel and rhythm. During the '60s and early '70s, his trademark right-hand-driven 16th-note groove was in constant demand among artists like John Lennon, George Harrison, Traffic, Joe Cocker, Carly Simon, Delaney & Bonnie, and Eric Clapton. He was the drummer on Derek & the Dominos' Layla & Other Love Songs and the early Clapton solo albums. He wrote the beautiful second half of "Layla," all lush piano chords and trembling guitars. Unfortunately, Gordon's remarkable talent was mired by mental disease that tracked him from the age of seven and eventually ended his career. He heavily influenced two other drummers, though: Jeff Porcaro and Jim Keltner.

According to Keltner, "When he was on, he exuded confidence of the highest level-incredible time, great feel, and a good sound. He had everything." "On Pretzel, " says Porcaro, I played on 'Night by Night' and Gordon and I played double drums on 'Parker's Band.' Gordon was my idol. Playing with him was like going to school. Keltner was the bandito in town. Gordon was the heir to Hale Blaine. His playing was the textbook for me. No one ever had finer-sounding cymbals or drums, or played his kit so beautifully and balanced. And nobody had that particular groove. Plus his physical appearance - the dream size for a drummer - he lurched over his set of Camcos."

In retrospect, it's stunning to realize that Jeff Porcaro was only nineteen years old when he recorded Katy Lied . The album is a tone poem, a surreal view into the minds of Becker and Fagen. The grooves are varied, from the pumping shuffle of "Black Friday," to the 3/4 jazz waltz of "Your Gold Teeth II," to the slow blues of "Chain Lightning," to the perfect time of "Dr. Wu." Porcaro enjoys the distinction of being the only drummer Steely Dan used whose final product was always kept without being overdubbed by another player. The versions he recorded always made it to the final master tapes.

"On

Katy Lied, " Jeff recalls, "all that went through my mind was Keltner and Gordon. It was do or die for me. All my stuff was copying them. For instance, on 'Chain Lightning', all I thought about was the song 'Pretzel Logic,' which is Gordon playing a slow shuffle. On 'Doctor Wu,' I was thinking of

John Guerin, especially those fills going out between the bass drum and toms. He'd do it in a bebop style. Guerin was on

Joni Mitchell's

Court & Spark , which was in that same Steely style. Things were getting cool and bent.

"'Your Gold Teeth II' is a song with lots of bars of 3/8. 6/8. amd 9/8. And it's bebop! I could swing the cymbal beat and fake it, but that always bothered me. After recording it, Fagen gave me a Charles Mingus record with Dannie Richmond on drums. It had a tune that was full of 6/8 and 9/8 bars. I listened to that for a couple of days, and we tried it again and it worked. What a cool thing! The ride cymbal on that, and on the whole record, is an old K Zildjian my dad gave me. Unfortunately, all the cymbals are clipped and phased on the album because the DBX didn't work. That was real heart-breaking for those guys.

"On 'Black Friday' l was again thinking of Jim Gordon, my shuffle champion. I got real frustrated trying to play this, and just threw a big tantrum. 'I'm the wrong guy! You should get Jim Gordon,' I told Gary Katz. After walking around the block three times, cursing myself, I came back in and cut it. That guitar solo is Walter on an old Fender Mustang guitar with rusty strings, That's a bad-ass solo, man."

And what about those multitudinous takes? "Oh yes!" laughs Porcaro. "Although their charts were meticulously written out for ensemble figures and general drum feel, there were no click tracks or sequencers, so you're going through the track hoping for the magic take - up to thirty takes same days.

"When Steely Dan's first album came out, I flipped" recalls Porcaro. I thought they were the Beatles of California. I was always scared shitless playing for them. They were very demanding - not in a malicious way - but everyone respected them so much. You felt you were playing on something really special. When they were happy, it was great to see. It meant you'd accomplished something."

Once again, Becker and Fagen continued to raise the stakes. On The Royal Scam, they took rock 'n' roll arrangements to a new level of craftsmanship. Dealing with the most highly skilled musicians available, including the Pharaoh of Funk, Bernard "Pretty" Purdie, the record had a sense of risk-taking and new ground being broken.

"Green Earrings," for example, sounds like a big band arrangement played with rock 'n' roll instrumentation. There's a lot of depth to the music, and every listening reveals yet another nuance, another layer of sound. Purdie's slam-dunk, slippery funk is pure joy. The grooves float and sting effortlessly above, below, and through the music. His drumming on songs like "Kid Charlemagne" and "The Fez" is the stuff of legend.

"With me, they wanted something very specific," says Purdie with a quiet tone of voice that makes him sound like a riverboat gambler. "They had already recorded 'The Royal Scam' with other drummers, so I had to overdub. I stuck to the original patterns, but they wanted what I could do. It was a heavy situation. I wasn't uptight about trying to impress them, I was just doing my job. They knew my earlier work, so they wanted to hear my take on their music

"They were very strict to the point of super precision," Purdie recalls. "Really picky. They wouldn't take no for an answer and they wouldn't accept mistakes-period. It was truly frustrating in the beginning. I come from the school that when you feel good about what you've done, it's hard to do better. It only goes downhill from there. I learned to curtail my own feelings and just wait. They wanted it their way, so you had to do many takes."

Drummer Rick Marotta, who already had had super-session duties at that time with Linda Ronstadt, Paul Simon, John Lennon, Jackson Browne, James Taylor, and Tom Scott, didn't know who Steely Dan were when he sat dawn to record "Don't Take Me Alive". "I remember I wanted to get in and out as soon as possible. Larry Carlton and Chuck Rainey were there, pretty much business as usual. Then they counted off this tune...the first thing I heard was the lyrics 'agents of the law/luckless pedestrian,' and I almost stopped playing. I thought, 'I'm listening in my phones to this guy who can really sing, and the tune sounds amazing, and the band is amazing,' it was just... different . You have to kiss alot of frogs when you're a studio player. After that I had to stop and collect myself: ' This is real.' Every time I went in with them I knew it was going to be something really historic.

"They were the most demanding of anybody I've ever worked with," Marotta says. "Donald was like the Prince of Doom. For instance, I'd walk in the control room and it would sound unbelievably great, and he'd just sit there, looking at the floor, saying, 'Yeah, I guess it's okay'.

"0n 'Dont Take Me Alive', there's one backbeat in th 16th or 17th bar that was a little softer than the others. I'd say, 'Donald, show me where.' He'd wait for the tape to come around and he'd point it out. 'Right..... there .' He'd pick the same spot out each time. He wasn't crazy, he was just so microscopic. Walter was as well. It was beyond my imagination how anybody could be so focused for so long."

Aja is the most popular of all the Steely Dan recordings. Four of its seven tracks were radio hits with a broad spectrum of appeal. Musicians had a field day with the title track, which had powerful solos from Wayne Shorter and Steve Gadd. Gadd, it seems, was the ultimate foil for the Dan's demanding assault on a musician's psyche. For 'Aja' he sightread the entire seven-minute chart perfectly, solo and all, by the second take. An article at the time quoted Fagan as saying, "I was stunned. No one had ever done anything like that before. I couldn't believe it."

Once again, the new record surpassed the expectations of their legion of fans, each song a fully realized world unto itself. 'Black Cow,' with its silly chocolate bar subject, was gently nudged along by former Lawrence Welk drummer Paul Humphrey. (Humphrey's group, the Cool Aid Chemists, had a soul hit in I97l) The laid-back Southern aroma of "Deacon Blues" featured Purdie. The incredibly catchy "Peg" featured a fiery, sassy drum track from Marotta. "Home At Last" showcased the classic Purdie shuffle, supporting a sad tale of remorse and fear. "I Got The News," a dotted-l6th-note bounce-fest that sounds like early hip-hop, was Ed Greene's only track for the Dan. And "Josie," the story of the welcome shown returned a town prostitute, is Jim Keltner's minimalist tour de force of taste and style. With it's perfect balance of memorable songs, outrageously superb performances, and immaculate production, Aja is Steely Dan's masterpiece.

"When I first heard 'Josie' back I didn't like it," said the ever-sunglassed bandito. "It was a funny groove. It was such an odd song, especially for that time. In retrospect, I love the sound of it, the feel. Fagen had been through full sessions with other drummers for the same song. He was such a commanding musical figure, you knew that when he told you to play a little figure, you'd better play exactly what he wanted. That was a lot of pressure on me at the time, but I relished the musicality of it. I concentrated heavily. It was a five page chart with no repeat signs.

"As for that fill near the end, it was a bar of 7/8. That's definitely not something that I would've played. That figure was written on the paper, it was totally Fagen's thing: I wish I could get a copy of that chart. I've had more drummers ask me about that lick. I was playing a 5x14 Ludwig Vistalite snare drum, a Super Sensitive---weird instrument.

"Later, they wanted me to overdub something over the breakdown, but they didn't know what. The beauty of those guys is that they truly wanted something weird. So I played this garbage can lid with rivets in it that I'd been given for Christmas. They liked the way it sounded, so it became a part of the song."

Though Keltner cut "Peg," his track didn't make the final pick. "You do have an advantage in a way, if you come in behind someone else. The writers have already been through the song, and they have a better handle on what they want. I didn't do a good job on 'Peg,' it just didn't work."

Consequently, Rick Marotta's take on "Peg" was the one Becker and Fagen went with. "Chuck Rainey and I got into this groove that was really unstoppable," Marotta recalls. "We had this groove for the verses, and then the chorus came and everything just lifted. It just went that way every time. Everything was just working - my hands, my feet - it was just one of those days. On 'Peg,' I could hear every single nuance that I had played, as well as what everyone else had played. What amazed me was how they could mix those records like that. You could hear everything perfectly. The snare on that song is an old wooden Ludwig with Canasonic heads. It used to be Buddy Rich's drum."

After a long wait, Gaucho was released to an eager audience. While the music was of the usual high leveI, it should be noted that, drum-wise, this album is much simpler than previous ones. Except for a Purdie shuffle on "Babylon Sisters" and Porcaro's odd-meter forays on "Gaucho," the rhythms are all 8th-note grooves. No cranking shuffles like "Black Friday" or jungle grooves like "I Got The News." Part of this might have been Becker and Fagen's desire to fully explore their WENDEL, a sequencing tool that could quantite, sanitize, and generally sterilize a drum track.

"That was Roger Nichols and the computers," says Marotta, who played on "Hey Nineteen" and "Time Out Of Mind". "WENDEL wasn't perfected then, so occasionally it was a little stilted. They were experimenting, taking little snippets of what we played and looping it."

According to Porcaro, "That's at a point when drum machine technology was just rearing its ugly head. There was a lot of talk about the future of quantizing and sequencing in real time. To a perfectionist, that was all really cool stuff. The title track was done to a Urei click. In fact it was all Urei except 'Hey Nineteen,' which is WENDEL."

The title track, which Porcaro played on, is an epic bit of Mexican-inspired music, full of enigmatic lyrics and romantic female choruses. The Dan had perfected their recording approach by this time. "From noon till six we'd play the tune over and over and over again," says Porcaro, "nailing each part. We'd go to dinner and come back and start recording. They made everybody play like their life depended on it. But they weren't gonna keep anything anyone else played that night, no matter how tight it was. All they were going for was the drum track." (The final product was a combination of 46 edits.)

"Hey Nineteen," the album's big hit, is a yearning for young love. "Everyone talks about that song, but it was a complete departure," says Marotta, "totally different from any recording we'd done. It's a great song-- a classic groove, a definitive pocket. There are also other songs from those sessions that will never come out. I played on one song called 'Cooly Baba' that was really unbelievable. On the first batch I did with them in New York, there were some classic ballads, but they were never released.

"They were using up to six different rhythm sections for the same song," Marotta continues, "so I would beg them to just do it with me. So Donald and I did 'Hey Nineteen' and 'Time Out Of Mind,' just the three of us - the click track, Donald, and me. He sang and played piano, and I played the drum track. It took no time. That's what's on the record."

Bernard Purdie sheds some light on how Becker and Fagen worked when things got difficult. Laughing his sinister laugh, "I'll put it to you this way. Walter was the more vocal one, while Fagen might be having a fit inside. If he didn't like something. he would jump on Walter and Gary Katz. Walter would try to explain. He was good at taking the heat and being the heavy. We could tell who liked the song the most, who had the most influence on a particular track. People can say what they want, but Walter was the heavy and Katz was the compromiser. He was able to hold the two of them together in getting things they both wanted."

In the years that have passed since the last Steely Dan release, Becker and Fagen have kept busy. Becker produces West Coast jazz, while Fagen relives his childhood on his Rhythm And Soul Revue shows. Fagen even issued a live recoding of "Pretzel Logic." Talk of an impending Steely Dan record continues to float around, with both Dan-sters participating this time out. And there's a Steely Dan box set in the works, complete with outtakes. But if you haven't heard those first seven albums and all that wonderful music, what are you waiting for? You've got a lot of catching up to do.

Potem je tu še filmska glasba, pa še kakšen singl, ter seveda njune solo plošče.